We have now come to the end of the first phase of fieldwork for the Disconnected Infrastructures project, based in Thiruvananthapuram, the capital city of Kerala.

We set out to explore the links – and disconnects – between women’s experiences of the city, public safety and urban infrastructure, and our initial findings have been both surprising and illuminating – highlighting the different ways in which women perceive safety, gender-based violence, public and private space and issues of infrastructure.

The fieldwork consisted of a three-month study conducted with our project societal partner – women’s resource centre Sakhi – in a low-income neighbourhood within the city. The study was designed to a) deepen our understanding of the links between violence against women (VAW) and access to infrastructure at the neighbourhood level and b) develop the capacity of women from low-income neighbourhoods, in using digital technologies to better access urban infrastructure. After selecting our study site in a low-income resettlement colony located in the south of the city, we conducted in-depth interviews with 16 women, ranging in age, background and occupation, to try and understand their experiences of both their local neighbourhood as well as the city at large.

In addition to interviews, each participant was trained in using the Safetipin mobile app (our second project societal partner) and we conducted a manual safety audit of their local neighbourhood or places in the city where they spent time using the Safetipin mobile application. Most of the women we trained were unfamiliar with app functionalities overall and while some were intimidated by the app itself, most the participants stated they found the experience of the audit itself interesting, useful and in some cases were eager to learn more about how to use the app regularly. Mobile phone use seemed mainly restricted to social use and basic functions rather than perceived as a ’safety tool.’

Our main findings showed that for the women in the neighbourhood, issues of public infrastructure, specifically the local sewage and drainage system, and widespread substance abuse among men were of primary concern – these issues were far more frequently and vocally expressed than issues regarding domestic violence or VAW in public spaces.

In fact, when we explicitly asked the women, issues of VAW both in domestic and public spaces emerged as a secondary issue of concern. In the community we found issues of draining, lack of sufficient sewage systems, problems with public services in the neighbourhood directly affected women. As one woman stated:

“We are the ones facing these problems in the home while men go outside, are away from home for work, or enjoy themselves, or go drinking.”

Here, the gendered nature of infrastructural issues explicitly connects violence against women – both structural and physical (in terms of health impacts of poor sewage systems, and physical labour required to maintain poor sewage) and infrastructure in the city. The finding also shows the normalisation of violence in the women’s daily lives, such that it is considered to be low on a list of priority areas to address in the community.

At the end of our study, we conducted a community workshop, led by Sakhi and attended by our partners, within the neighbourhood in order to consolidate and further examine some of our findings, exchange knowledge with the women in the neighbourhood and seek ways to actively address the key issues raised in the study regarding infrastructure and VAW. Women in the neighbourhood where we conducted our study were invited to attend the three-hour afternoon workshop. A mix of participants from the study and other women from the community attended, ranging from elderly and middle-aged to women in their early thirties – some bringing their children or younger relatives with them.

The workshop started with initial introductions led by our local partner Sakhi, and an outline of the purpose of the workshop, to help increase our understanding of how urban infrastructure can be improved to enhance the safety of women in the city. The workshop consisted of three main activities described below.

1. Gender roles & norms

The first activity conducted was designed to invoke a discussion on perceptions of gender roles in the community. The participants were asked to collectively share their opinions and ideas on ‘typical’ roles of women and then men in society according to their own experiences.

In the discussion, many of the participants expressed ‘ideal housewife’ as one of the typical roles women took on in the community. Many women also listed aspirational qualities of women such as empowered, strong and capable of self-defence in times of crisis. When it came to typical roles of men, the participants most commonly listed substance abuse – mainly alcohol, and among male youth, drug use – and lack of responsibility or sense of care towards their families or society in general. The word ‘numb’ is repeated in the responses suggesting desensitisation among men perhaps induced or exacerbated by substance abuse.

This activity generated discussion among the participants about gender norms, the difference between aspirational and actual gender roles and expectations.

2. Mapping safety in the city

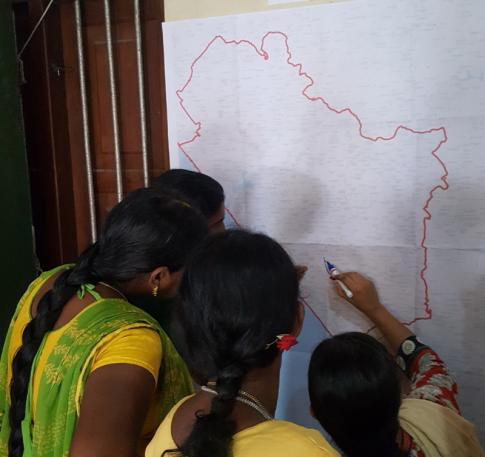

The second activity was based on the participants’ lived experiences of navigating the city and their local neighbourhood. The participants were presented with two maps – one of their local neighbourhood and one of the city of Thiruvananthapuram – and asked to mark out their daily routes for purposes such as commutes, errands, religious or civic duties and so on. On these routes, the participants were then asked to form groups and collectively identify areas they considered safe and unsafe – according to their own personal experiences and perceptions.

The activity highlighted the limited spatial awareness and mobility of many of the participants and provided an insight into how the city and its infrastructure such as public transport and public spaces are experienced by women from low-income neighbourhoods both within their localities and beyond.

3. Collective petition

The final activity of the workshop was based on efforts to try and translate the concerns raised by women in the community, into action. The two primary issues that emerged from study overall, and the workshop were: sewage and drainage problems in the neighbourhood and substance abuse. Issues of VAW – both in domestic and public spaces – emerged as a secondary issue in the discussions and interviews. The women explained that the waste management issues prevailing in their neighbourhood affected them directly, whereas men predominately spent time outside of the domestic sphere and thus did not have to deal with the issues on a constant basis in the same way.

Following collective discussion, the participants decided to develop a petition around the issue of waste management for the attention of the local municipality, calling for moves to address the issue of waste collection and poor sewage systems. Sakhi plan to take this petition forward; identifying the appropriate municipal body and representative and drafting a final petition collectively with community members.

Overall the workshop helped use engage with the community at a broader level and enabled Sakhi to build sustainable links with the community beyond the 16 participants we interviewed. The workshop discussions also helped us crystallise some of the findings gathered over the course of the previous three months. These include the widespread normalisation of violence – in both public and private spaces; the growing problem of substance abuse spanning different generations and how this helps create a continuum of violence against women both in their homes, and in public spaces. Finally, the need to be attentive to how women experience urban infrastructure – or lack of – in their daily lives at both the intimate, domestic scale as well as at the broader city-wide scale in seeking to address disconnected infrastructures and violence against women.

Please explore the community participatory workshop Wakelet story here.

By Dr Nabeela Ahmed, Project Postdoctoral Research Associate, Urban Futures Research Group, Department of Geography, King’s College London

Reblogged this on Urban Futures Research Domain and commented:

Report from community participatory workshop in Trivandrum on the ‘Disconnected Infrastructures and Violence Against Women’ research project

LikeLike